For Internal Audit Credibility Must be Rooted in Objectivity

September 30, 2021

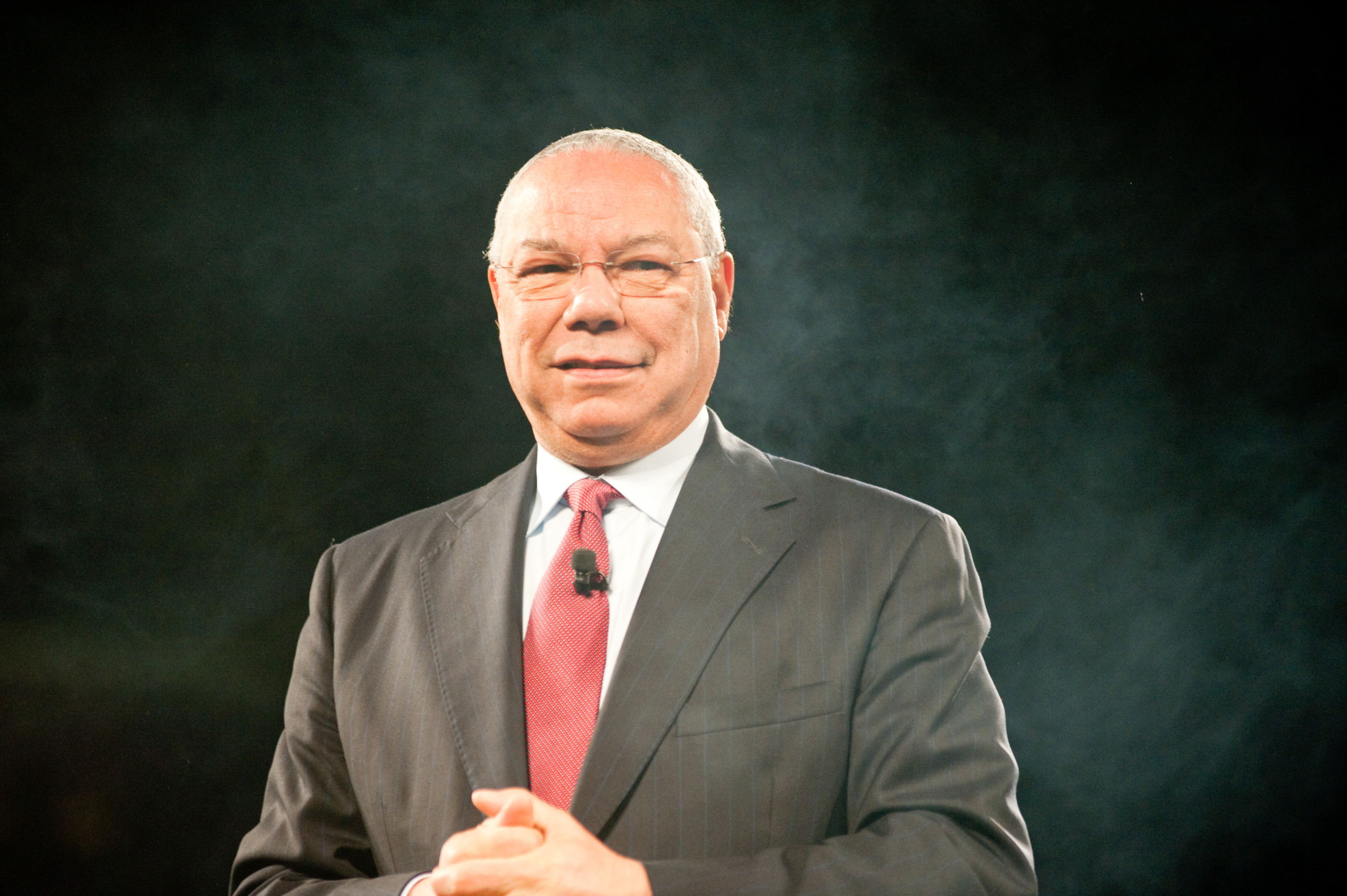

Five Leadership Lessons Colin Powell Taught Me

October 22, 2021A recent headline from Reuters caught my eye: “Scandal-hit Credit Suisse names new interim heads of internal audit – memo.” According to Reuters:

“Credit Suisse (CSGN.S) has appointed company veterans Nitesh Patel and Roger Senteler as interim co-heads of group internal audit, Switzerland’s second-biggest bank told employees as it tries to recover from grave risk-management lapses.”

I don’t know either of these gentlemen, and certainly have no reason to question whether the arrangement will work out – especially on an interim basis. However, the more I thought about the development, the more I asked myself: Can a company have two chief audit executives at the same time?

Without a doubt, the role of the modern CAE involves complex and daunting responsibilities. The CAE must not only assemble and lead a talented team of internal audit professionals, they also must win and sustain the trust of the board and senior management. That can demand courage, particularly in the face of adversity. As I have observed over the years, a CAE must be willing to “sail toward storms” and “push on closed doors.” They must be equally capable of providing assurance, insight and advice while serving as a change agent. Finding all of those traits in a single individual can be formidable, but is there a reason why two such talented and competent individuals could not serve as co-CAEs?

There are notable examples of large companies that have two CEOs. Nexflix is one, and Fortune magazine reported last year that as many as 13 of Fortune 500 companies had co-CEOs. In fact, a recent article from TechCrunch+ argues that, sometimes, “Two CEOs are Better than One.” Among other arguments put forward by TechCrunch+ is that two CEOs can divide and conquer to accelerate the learning curve, with each focusing on core components of the business. Having been a CEO for 12 years, I’m not sold on the long-term viability of having dual CEOs. However, if large, successful companies can effectively navigate such a course at the highest level, then it would be foolhardy for me to argue that two CAEs cannot work.

That said, having spent almost 20 years also as a CAE, my opinion is that it is not an optimal arrangement.

The very definition of “chief” (the head or leader of an organized body of people; the person highest in authority) would appear to refute the idea that there can be two. The International Standards for the Professional Practice of Internal Auditing specify numerous responsibilities for the CAE, including managing the internal audit function, planning and communication. I do believe that two individuals could collaborate to fulfill the technical responsibilities of the CAE role. But I also think that challenges could rise in the CAE’s crucial role as a “trusted advisor” to the board and executive management. Even two individuals who are extraordinarily aligned philosophically could face hurdles in inspiring and leveraging the trust that should be invested in internal audit. Over the years, I have evaluated internal audit at many organizations where a strong, personal relationship between the CAE and CEO, CFO or audit committee chair was instrumental to internal audit’s success.

While the culture of some companies might make a dual-CAE arrangement feasible, underlying issues could create conflicts. For example, if internal audit took an unpopular position or issued a damaging audit report, management might react with a “divide and conquer” tactic, appealing separately to each of the CAEs for reconsideration. I feel that, in response, the two CAEs would need to stand as one and not take individual sides.

My greatest concern is that personal dynamics in a dual-CAE setup could prove corrosive and present unintended risks over time. The Fortune article on co-CEOs cited research by professors from the Universities of Virginia and Michigan that concluded:

When higher-power individuals work with other higher-power individuals, destructive power dynamics may emerge, which harm group performance. Researchers noted that paranoia can creep up as bigwigs fret that their personal clout is under threat from their peers. The researchers observed that can lead to preemptive power moves against others in the group. Finally the research concluded that people in top jobs aren’t used to having to check each decision with someone else. It’s hard for them to be in that trusting relationship.

That assessment may be a bit dire in the context of joint CAE arrangements, but it would be a risk, nonetheless.

I always pull for the success of every internal audit function. I wish the newly appointed co-CAEs of Credit Suisse the best as they seek to help the company recover from its recent challenges.

I welcome your thoughts. Would a co-CAE arrangement work in your organization?

I welcome your comments via LinkedIn or Twitter (@rfchambers).